Reading and writing have been staples of basic communication for thousands of years. One might wonder what kind of effect the written word had on the Church over the centuries. But perhaps a better-crafted question might be what happened to Christianity when words became “printed and replicable” on a large scale.

Following what we discovered in our previous blog about Marshall McLuhan’s communication theory “the medium is the message,” it’s not a big stretch to suggest that the technology of writing, because of its emphasis on visual cues, shapes the way we think regardless of what is written. That’s right, writing was, and still is, a form of technology. It requires the use of special tools such as pen, paper, brushes, and skins. Writing also requires human invention of a symbol system that needs decoding and encoding.

With this in view, it’s possible the written word has the power to restructure the worldview of an entire society. And as we shall see, it also clearly had a similar effect on the Church.

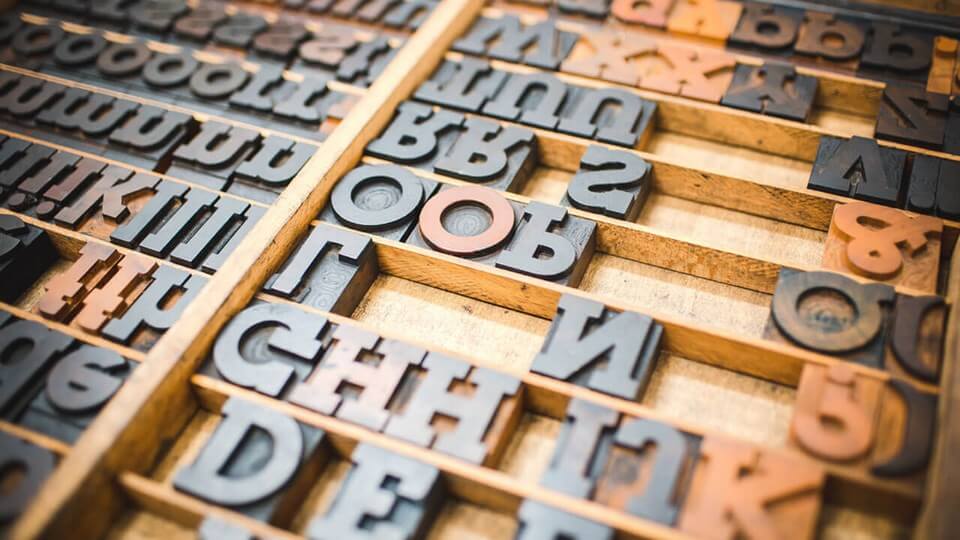

Of all the media inventions in history, few can rival the amazing and dramatic effects of the written word and eventually its adaptation to the printed word.

History of Print

China and its Far East neighbors crossed the tape first in the technology of printing. Asian cultures had block printing 800 years earlier and movable type 400 years than European cultures. Yet, the printing press had none of the same liberating intellectual effects it had in the West. Why?

Because the spoken languages of Eastern and Western societies are symbolized in a completely different format. China in the East uses pictorial writing to read. A single symbol or character represents an entire word or concept and often bears a visual resemblance to the thing it describes. For example, the Chinese word for “brave” looks like a man in action.

Europe in the West employs a phonetic alphabet to read. It is based purely on phonemes or vocal sounds that are pronounced in a certain order to create meaning. In other words, Western words and language on paper are completely abstracted from reality. For example, the English word for “brave” …B-R-A-V-E…is just a collection of random lines and curved shapes used to create meaning when put together in a linear fashion from left to right.

So we see this striking contrast between written languages: Chinese, which is ideographic, non-linear, concrete and intuitive. And English, which is phonetic, linear, abstract and anything but intuitive!

And both the absence and abundance of these two language systems profoundly impacted how the Western European Church communicated the Gospel to the world in which it lived. The Greeks created their own version of the phonetic alphabet around 700 B.C. and had mastered it by 400 B.C. Its slow but steady infiltration across Europe was abruptly cut short in the 4th century when papyrus supplies ran short. Literacy rates plummeted and Europe returned to a dominantly oral culture. The Church responded in an increase in iconic displays inside the walls of its edifices and fused on its stained colored glass windows.

I visited many of the old cathedrals when I was growing up a military kid in Europe. They are stunning and majestic. The Church during this period and the centuries that followed put heavy emphasis on mystical and sacramental theology.

The Invention of the Printing Press

But literacy was reintroduced on a mass scale in the 12th century when Chinese trade routes made famous by the Silk Road brought paper back to Europe. A couple hundred years later, the stage was set for one of the most important inventions in world history. Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press. With this simple invention Gutenberg set off an explosion of such overwhelming power that we continue to feel its reverberations today. Literacy and independent study exponentially increased. And in 1517 Martin Luther had the communication tool he needed to launch the Protestant Reformation.

But strangely, immediately following this groundbreaking invention in the West, something unusual happened in the world of media: NOTHING! From the 15th century until the early 19th century, no new communication technologies were introduced to alter the way information was delivered.

Western culture became entrenched in individualism, abstract thinking, and objectivity. Why? Because people on a large scale could now carefully read the words of great thinkers for themselves….and read the words of the Bible for themselves. Meditate. Ponder. Consider. Muse.

The old medieval worldview slowly began to fade into the background: the tribal, the mystical, the sacramental experiences…They never fully dissolved but their place in Christianity was realigned and reprioritized.

How Print Created the Modern Church

Think about what we’ve just laid out here: these changes were caused as much by the form of the new medium—the printed word—as the content itself! Was the content of the print all “new information?” Not at all. More than half of all printed books in these early centuries were rare medieval or ancient manuscripts. But a new worldview was slowly emerging from the wave left by the power of the printing press. Shane Hipps, author of The Hidden Power of Electronic Culture offers four primary ways in which printing created the modern church.

1. Print made mankind more individualistic.

We could now think in isolation. The community is no longer “needed” to retain teachings. There was a rise in the interest of “personal” aspects of one’s faith. Christian writings created the ability to “freeze” a dynamic and fleeting inner thought. Print provided some distance form a strictly “emotional” life stirred up by a season orator or preacher. The result was that the church community became little more than a collection of individuals working on their personal relationships with Jesus. The danger at the time was moving that line from personal to private, which is completely opposite of the Biblical understanding of what it means to live as one of God’s people in the Earth.

2. Print introduced the notion of objectivity.

We can now judge something outside of ourselves. We can act without reacting. We can slow-cook and ponder an idea, something that’s often difficult to do in a spoken conversation or while trying to listen to a long speech or sermon. In orally dominated cultures, there is virtually no way to separate oneself from one’s ideas. The notion of objectivity almost never changes. The danger of objectivity is that it can leave little room for a truly subjective experience with God because there can be too much reliance on written propositions. It’s one thing to read and ponder the amazing truths of the book of Romans but quite another to be undone with both the conviction of sin and the exhilaration of knowing one is personally forgiven by grace while in the presence of the Spirit of God.

3. Print made mankind think more abstractly.

Information in an oral culture had to be repeated, be formulaic, and be concrete. Printing freed the mind for original and creative thought. By that I mean people were no longer bound by the pragmatic concern of retention. This shift in perception and understanding caused the approach to theology and faith to be more abstract as well. The pulpit began to slowly overshadow the sacraments like baptism and communion. Preaching became the focal point of a worship service in the modern Protestant church. Sermons became more abstract, lengthy, verbose and dense.

Theologian Jonathan Edwards was well known for preaching up to four hours knowing his congregation had Bibles in hand in which they could follow along. George Whitefield had sermon titles that would have been too long to post as a 140-character tweet! One message he titled: A Preservative Against Unsettled Notions, and Want of Principles, in Regard to Righteousness and Christian Perfection. Sounds more like a doctoral dissertation than a sermon. The message itself was written with the technical language characteristic of a collegiate academic paper. You might presume these sermons were intimidating for the common audience. On the contrary, these were regarded as great revival sermons of the day and served as the seedbed of the Great Awakening in America.

Conclusion

The danger of this printing influence is that when taken to extremes, abstract thinking becomes detached from the physical needs of the world and the Church. Biblical doctrine and systematic theology, without accompanying kindness of heart, can breed Christians with no compassion.

In Part 3 of this series on “the medium is the message,” we’ll take a look at form of communication that is pushing society, and possibly even the Church, beyond the modern age into what many today are calling a post-modern culture.

But before we conclude, what are your thoughts on this? Do you think the printed word has helped or hurt the modern church? Let us know your thoughts by commenting below.

Want more ThoughtHub content?

Join the 3000+ people who receive our newsletter.

*ThoughtHub is provided by SAGU, a private Christian university offering more than 60 Christ-centered academic programs – associates, bachelor’s and master’s and doctorate degrees in liberal arts and bible and church ministries.